I traveled to Arizona last weekend to run an ultra, the Whiskey Basin 88K around Prescott, which I’ll blog about next time. For now, I want to share how revisiting the Southwest boosted my motivation to raise awareness and support for something much bigger and more important than just running—something that represents hope for future generations.

It has to do with the Grand to Grand Ultra, but not the event itself. Rather, its setting.

I find myself daydreaming about returning to run the Grand to Grand Ultra in September—a 170-mile weeklong, self-supported race that I ran in 2012 and ‘14—and visualizing the Southwest’s wide-open, remote topography in northern Arizona and southern Utah, a landscape that makes me feel tiny yet tough.

I yearn to immerse myself once again in those baking-hot plateaus, where rocky buttes colored crimson terra cotta jut up from the desert floor, and to climb those earthen walls and pick through a forest’s prickly brush and piñon, feeling animal-like with all senses alert. I’ll once again scuttle over slickrock and slog through sand, each day logging at least a marathon, with the hardest 50-miler I’ve ever done on Day 3, carrying all my food and sleeping gear for the week in a pack.

All the while, I’ll be in awe of the vastness and wilderness of this little-traveled swath that spreads through the center of what’s called the “grand circle” of national parks, Grand Canyon, Zion and Bryce.

Most of us know about and value America’s celebrated national parks, in the Southwest and elsewhere, but we collectively care less, or at least understand less, about the millions of acres of public land outside of the parks, much of it managed by the Bureau of Land Management. I’m doing this race again less as an endurance competition, more as an opportunity to revisit and revere this region up close, and ultimately do what I can to help protect it.

Where am I?

In 2012, the first time I ran the Grand to Grand and saw so many miles of the West’s undeveloped acreage up close and by foot, I gained a new level of appreciation and curiosity about it. Trekking solo on remote segments of the event’s route, totally off the grid, I’d occasionally ask myself, Where am I? What is this place even called? When I plugged back into civilization, I tried to educate myself more about it.

Fast forward four years. I was on a flight to Vegas, to rent a car and drive to Kanab, Utah, again, this time for a trail-running event called the Grand Circle Trail Fest, and I was thinking about how all the pieces of land in the region fit together—what’s what, between the national parks, state parks, wilderness areas and monuments.

I knew the Grand to Grand finishes in a state forest overlooking a magnificently sculpted, multilayered expanse known as the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and I had just read an article that helped me understand what “national monument” meant. The story, by ultrarunning coach Ian Torrence in iRunFar.com, was called “A Trail Runner’s Primer on Public Lands,” about the federal government’s relationship to America’s public land and the agencies that manage them.

Serendipitously, I struck up a conversation with a woman in the seat next to me, and she said she worked for the Durango-based Conservation Lands Foundation, the only nonprofit organization dedicated solely to protecting, restoring and expanding the National Conservation Lands.

What are the National Conservation Lands? Good question; I didn’t know myself until I asked.

America’s newest protected public lands

The National Conservation Lands are more than 36 million acres of protected public lands, rivers and trails mostly in the West and Alaska managed by the Bureau of Land Management. They include 28 National Monuments, including Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante.

Bruce Babbitt, who served as Interior Secretary under President Clinton, established the National Conservation Lands in 2000, which classified certain areas within the BLM as deserving of special protection, restoration and conservation because of their natural, historic and cultural value.

The creation of the National Conservation Lands represented a shift in the BLM’s mission, and a victory for anyone who cares about conserving open space for wildlife and recreation, and preserving the historic and cultural treasures found in many of these places. During the prior half century, since its founding, the BLM managed more than 250 million acres of federal land mainly to use it, not to leave it untouched. These uses include mining, logging, grazing, and oil and gas production. When the government declared that more than one-tenth of this public land would be off limits to destructive use and worthy of permanent protection, it was, simply put, a big deal.

You can see a map of the National Conservation Lands here and here. Check it out—I find it inspiring to learn about protected public land, full of trails for exploring; for example, I knew about and have visited the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, but I hadn’t realized until I looked at those maps that right next door is the 62K+-acre Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area.

Of course, none of this special protection happens overnight or without a fight. And more areas are worthy of the safeguarding that comes with the National Conservation Lands designation. Which brings me to the real reason I’m writing this: to throw my support behind the Conservation Lands Foundation and appeal to you, too.

I’ve launched a campaign to raise at least $10,000 for the Conservation Lands Foundation between now and when I run the Grand to Grand Ultra, and I sincerely hope you’ll support my online fundraising campaign with a donation.

Since its founding in 2007, the Conservation Lands Foundation has been at the forefront of protecting and expanding the National Conservation Lands. It does this in part by coordinating and supporting the efforts of some 70 “friends groups”—grassroots groups throughout the West working at the local level to advocate for public land protection and restoration (see here for a list of all the groups in Conservation Lands Foundation’s Friends Network).

Last year was a particularly busy year, as the Trump administration severely cutback the land designated for protection in Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments. Conservation Lands Foundation has been fighting through litigation and public advocacy to uphold the original designations for these national monuments.

(I’ll wait until May to write more about that controversy, because May 9 – 12 Morgan and I are traveling with a Conservation Lands Foundation group to hike around Bears Ears and learn more about what’s at stake and why we should care about these spectacular and sensitive areas.)

I want to spotlight instead some inspiring news about the National Conservation Lands.

The best news all year

In case you missed it, last month our polarized government did something truly amazing, which restores some of my hope for good government and citizen advocacy: with broad bipartisan support, Congress overwhelmingly passed and Trump signed into law the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management and Recreation Act. This landmark omnibus legislation, the result of years of work at the grassroots level that was supported by Conservation Lands Foundation, greatly expands and enhances protection for National Conservation Lands. It also permantantly reauthorizes the Land and Water Conservation Fund. It’s a win for water, wildlife habitat, cultural landscapes and the outdoor rec economy.

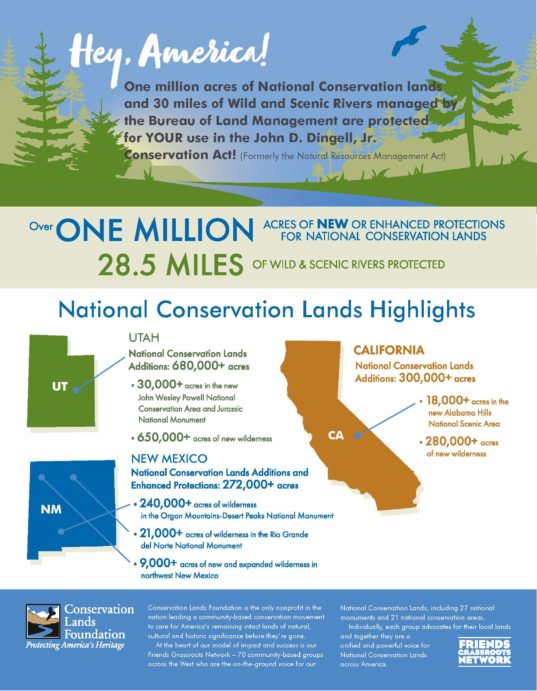

Here is a Conservation Lands Foundation infographic that sums it up:

So, will you join me in supporting this nonprofit group that is doing so much for the National Conservation Lands—for more than 36 million acres, 2400 miles of river, 6000 miles of trails throughout the West? If you have any question about the impact or management of the Conservation Lands Foundation, I hope you’ll read this summary of their 2018 annual report to understand their work better.

If you value the great outdoors and love to run trails through wilderness like I do, then I hope you’ll consider making a donation to my campaign through this link, and sharing this post or the fundraising page with others. I really want to do all I can to support the important work of this group, to help safeguard this remarkable public land that is so essential for so many reasons—for the wildlife and ecosystems, for the historic and cultural significance, and for the respectful recreation use by outdoor enthusiasts like us. For our kids’ kids.

And lastly …. if you want to learn more about the Grand to Grand Ultra, check out its site or my archived posts about it; it’s not too late to sign up and train for it. Get a copy of The Trail Runner’s Companion for all the info and inspiration you need to safely and effectively train for mountain/ultra/trail adventures.

Comments are closed.