I can’t stop thinking about my grandmother as I use my hands to crawl and climb above 13,500 feet on the southeast slope of Mount Sneffels, where the mountainside’s chunks of talus rock and loose scree transition to iron-tinged, broken-up boulders. A cascade of these large rocks, many of them wobbly and threatening to tumble down and strike me in the process, covers the passageway to the 14,150-foot summit.

Every footstep takes deliberate effort and represents a decision about where to step without slipping. Every labored breath, and every glance behind to survey how far we’ve come, leaves me lightheaded.

This summer, here in southwest Colorado near Telluride, I set out to improve my mountain running skills, to study this region’s history and to learn more about my family roots. This pilgrimage up Sneffels relates to all three goals.

A sign at the Yankee Boy Basin trailhead showing the southern route that Morgan and I took to the 14,150-foot summit of Mount Sneffels.

How in the world did my grandmother do this? What was is like for her, what was she thinking, and what kinds of clothes and shoes was she wearing in the early 1930s? Did her heart race like mine?

The final climb along Lavender Col, close to 14,000 feet, on Mount Sneffels.

I followed my husband Morgan and climbed up this crack to the summit.

My whole life, our family drove past the Sneffels mountain range in between Ridgeway and Telluride during summers spent here, and my dad mentioned on several occasions that his mother—Martha Middlebrook Bloom Lavender, who went by the nickname Brookie—was the first woman on record to climb it, in 1932. I would see the Sneffels massif miles away, from the comfort of our car zooming across Dallas Divide, but I couldn’t really get my head around her accomplishment, nor could I picture her.

The significance of Brookie’s climb, and her adaptation to the San Juan Mountains as a young New York transplant, didn’t sink in until I spent much of this summer studying her, along with my grandfather and my grandfather’s brother’s life, back then.

Finally, last Saturday, I got the chance to follow in her footsteps—sort of. It turns out, she ascended a much more difficult north-facing route up to Sneffels from Blaine Basin. My husband Morgan and I took an easier approach, from Yankee Boy Basin above Ouray, and still I struggled in the thin air to catch my breath, to calm my nerves and prevent injury while scaling those rocks. I’ve reached the summit of a 14’er only once before, Handies Peak on the Hardrock 100 Endurance Run course, and this Sneffels route makes the trail to Handies seem like a groomed parkway path.

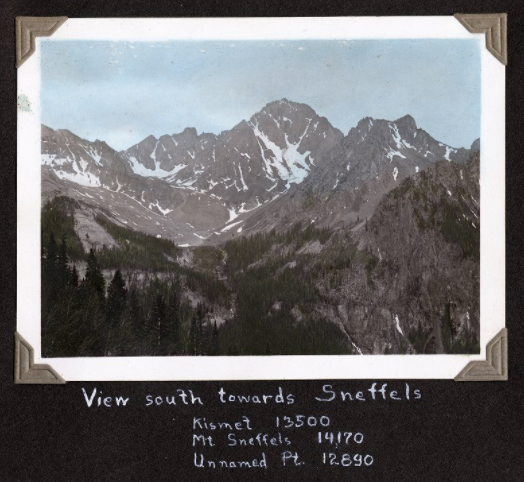

A photo of Mount Sneffels, circa 1931, from my great-uncle Dwight’s album.

The rock-strewn ridge we’re climbing—the final pitch to the summit—is called Lavender Col (a “col” being a ridge or saddle between two peaks). How many hikers have puzzled over that colorful name? It’s called Lavender not for any pale purple hue, but rather, in honor of my great-uncle—my grandfather’s younger brother—Dwight Lavender.

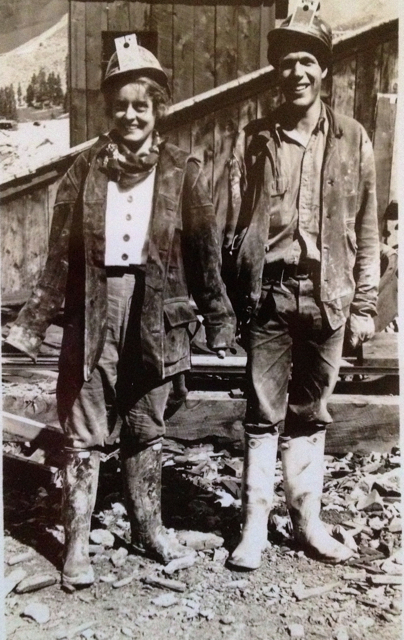

I’ve been studying how my great-uncle Dwight, my grandfather David and his wife Brookie experienced awe-inspiring adventures in the San Juan Mountains in the early 1930s, and they escaped to the mountains during time off from work just as the Depression delivered severe economic hardship to the region. They left academia to help keep the family ranch afloat, and, in the case of my grandfather, to work a series of odd jobs before getting a position for a season at Camp Bird Mine near Ouray. My grandpa explained in an interview: “I got $5 a day, from which 20 cents a day was deducted for board and 5 cents for insurance. Union people would come up to try to organize the guys, and the miners themselves would run them off. The waiting line of people wanting jobs would have stretched from the Camp Bird to Ouray. Those were hard times.”

The more I learn, the more I see parallels between their mountain escapades and the adventure that this generation’s mountain-running, dirt-bagging endurance athletes glorify. Like today’s Hardrock 100 ultrarunners who travel to Silverton weeks before the event to camp and spend entire days hiking and summitting the mountains, to adapt to the altitude and study the terrain, my relatives and their peers spent whole days testing their limits in the San Juan Mountains. But what my great-uncle, grandmother and grandfather did when they were 21 and 22 is more impressive to me than the mountain outings that my peers and I do insofar as they were trailblazers, scouting new routes, fashioning rudimentary gear and trying untested climbs.

Plus, I’m not a real climber. I can run and hike and get around big obstacles, but I am amazed by how my great-uncle and his peers really climbed these fearsome mountain faces.

My grandmother Brookie visiting my grandfather David to see where he worked in the Camp Bird Mine, likely summer of 1933.

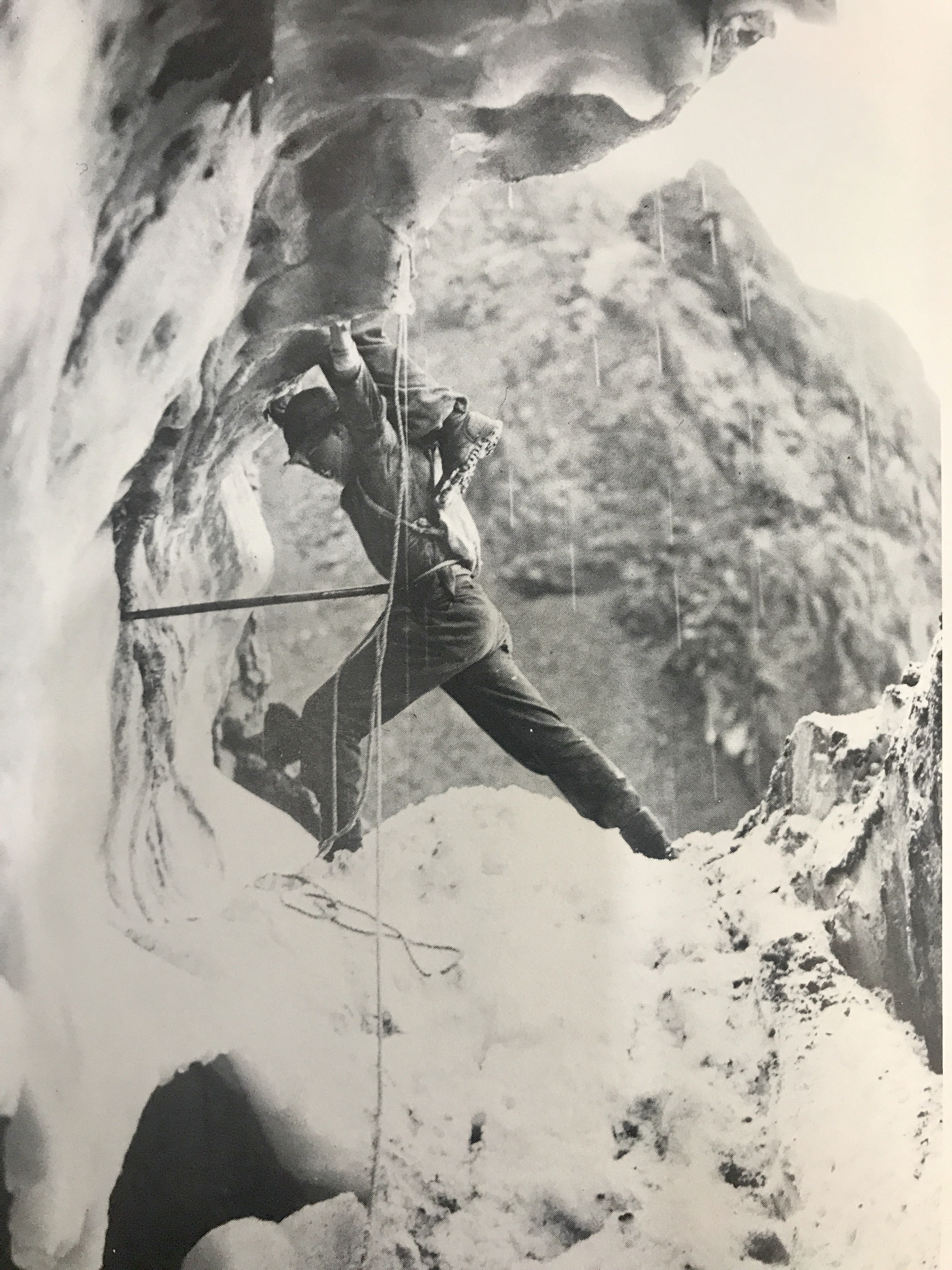

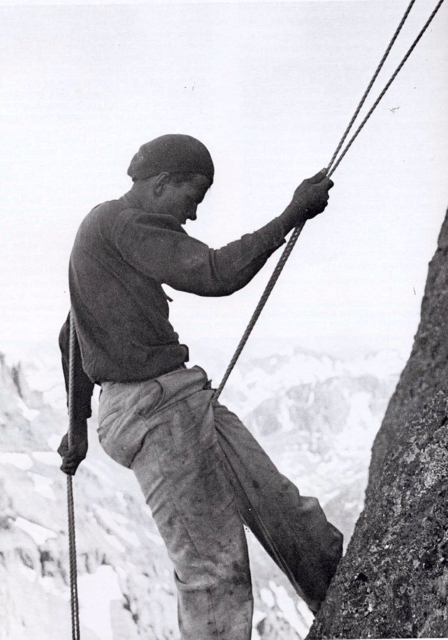

My great-uncle Dwight (my grandfather’s younger brother) giving a friend a leg up on ice on the Sneffels range, circa 1931.

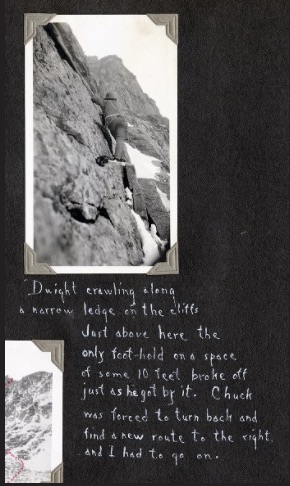

A photo and caption describing one of Dwight’s daring moves during a climb.

In 2017, Morgan and I approach Sneffels’ summit equipped with knowledge of the route, a trail marked by cairns, a GPS signal and an altimeter to measure our progress. We use trekking poles, hydration packs, good-quality shoes and layers of appropriate clothing for wet weather protection. We spot other hikers ahead and behind us, so we don’t feel alone.

Eighty-five years earlier, Brookie, David and Dwight set out for Sneffels under much different circumstances.

Dwight took the lead, because Dwight knew the Sneffels range better than probably anyone else at that time, and perhaps since.

My great-uncle Dwight climbing Teakettle Peak next to Mount Sneffels in the early 1930s.

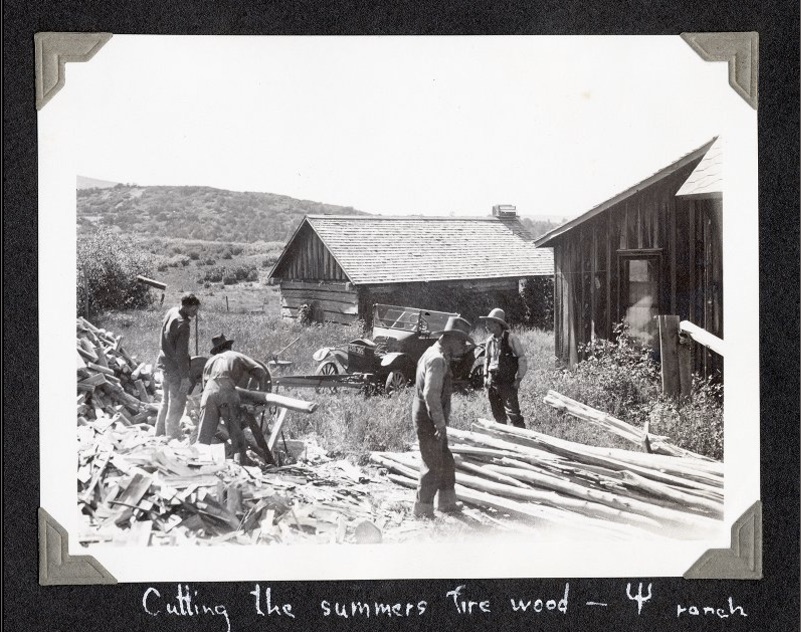

Dwight (born May 26, 1911) and my grandfather David (born February 4, 1910) were born in Telluride and grew up under the care and mentorship of their stepfather Ed Lavender. Their mother and their real father, David Painter—son of Telluride’s first mayor, Charles Painter—divorced when the boys were young; their mother Edith remarried Ed, who adopted the boys and gave them the Lavender name.

Ed Lavender was a mule-pack operator who transported goods to the mines above Telluride and Ouray in the early 1900s. When the advent of aerial tramways and automobiles cut into his packing business, he turned to cattle ranching and eventually expanded his cattle running from Southwestern Colorado across the Utah border. The boys attended boarding school to get a proper education but spent summers working on the ranch.

Work at Ed Lavender’s ranch, located about 20 miles southwest of Telluride.

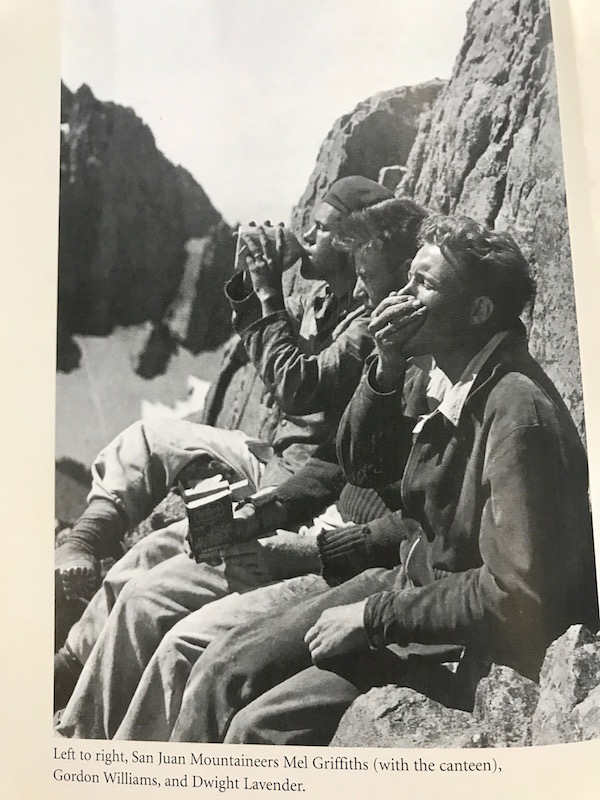

Dwight became an avid climber in his teen years and a founding member of the San Juan Mountaineers, a group of daring young men who explored as much of the San Juan Mountains as they could. Dwight’s friend Carleton Long wrote of Dwight, “Imbued with a love for the entire San Juan, Lavender nevertheless had his favorite mountain group. This was the Mt. Sneffels massif, with its enticing surroundings of unclimbed peaks and pinnacles. Lavender led successfully the only recorded ascents of the great north face of Mt. Sneffels—one of the most awesome slopes of ice and rock to be found in the United States. Struck by the total lack of any reliable maps in the Sneffels region, Lavender determined to survey this area accurately. Thus came to successful fruition in The San Juan Mountaineers Geological Survey which gave new and accurate elevations to Mt. Sneffels and dozens of surrounding peaks, and which recorded the existence of startling spires and pinnacles which will hold the interest of mountaineers for years to come.”

Dwight on the righthand side with the San Juan Mountaineers.

Dwight Lavender on the left with his friends Chester Price and Forrest Greenfield in 1930 after a successful ascent of El Diente (14,159 feet). Dwight and Chester organized the San Juan Mountaineers.

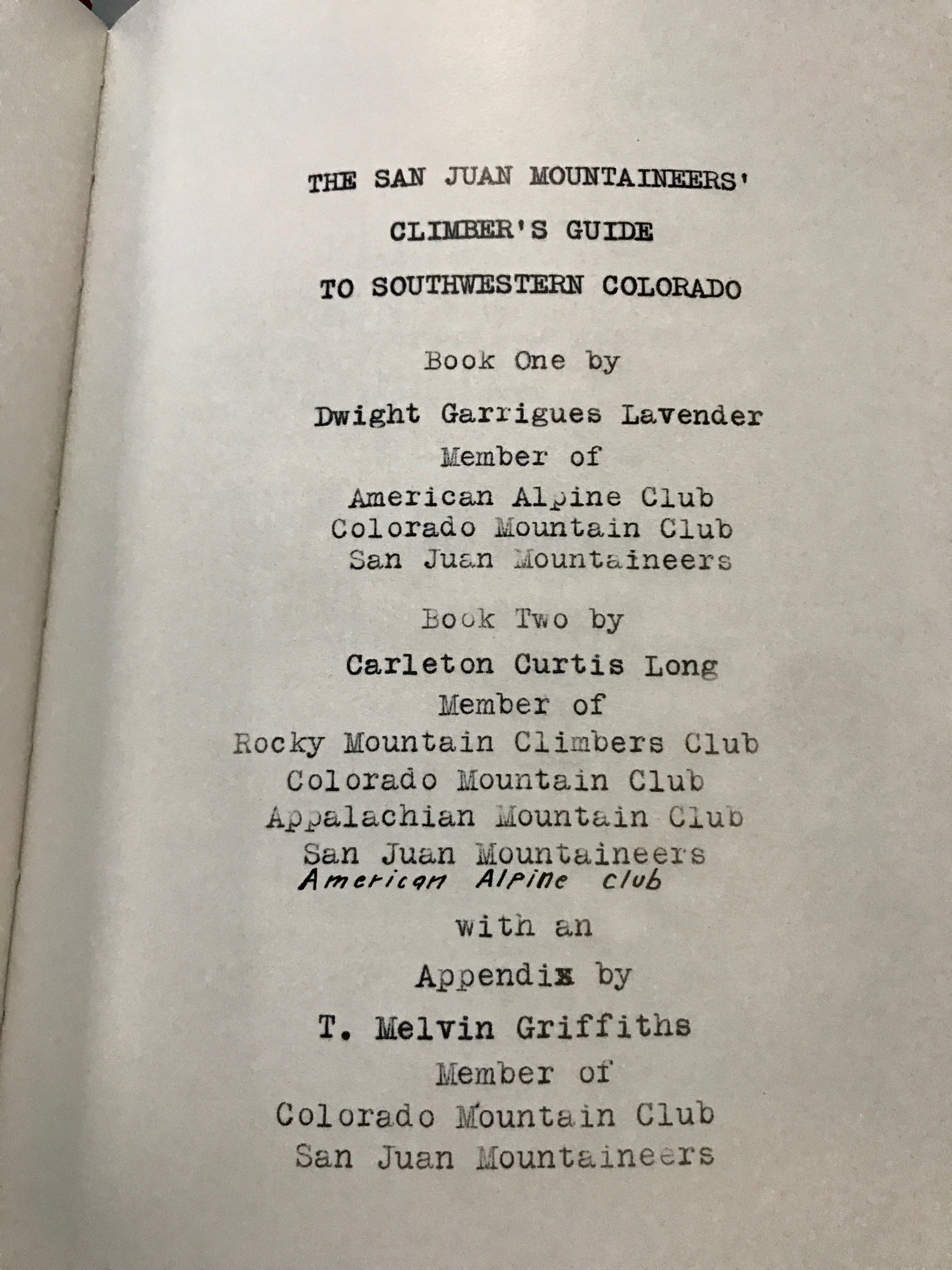

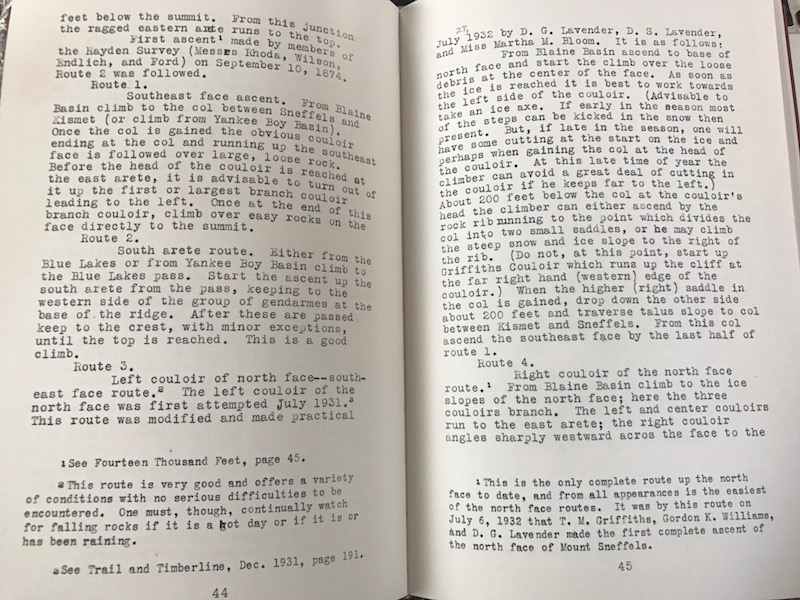

Dwight and a handful of others spent four consecutive summers climbing, route-finding and measuring these mountains, and in 1933 Dwight and two of his friends co-authored the first guide of its kind, The San Juan Mountaineers’ Climber’s Guide to Southwestern Colorado.

Only about four copies of this mountaineering guide existed in mimeographed form until the Colorado Mountain Club Press dusted off the manuscript and published a limited edition of it in 2008. This Climber’s Guide to Southwestern Colorado book, along with my grandfather’s autobiography One Man’s West,captured my imagination this summer and are the sources for the info that follow.

The title page to my great-uncles guide book, written in 1933 and republished in 2008.

Mountaineering—that is, teams of hikers exploring, climbing and mapping the mountains—developed in Colorado in the late 19th century because mining companies and the government commissioned geologic surveys to map and prospect the land. Finding routes to ascend and map 14’ers back then primarily had a scientific and economic purpose.

A generation later, Dwight and his peers continued some of this scientific work—exploring, measuring and improving the precision of the region’s topographical maps, especially of lesser-known 13’ers—but, they also made mountaineering more of a sport and a celebrated form of recreation. The advent of cars enabled them to drive to trailheads to bag as many peaks as they could. Weekend hikes with picnics became a part of the region’s social scene, as thrill-seeking young adults came together to form a group to summit a peak. (For more on this scene, I recommend the chapter “High-Altitude Athletics” in my grandfather’s book, One Man’s West.)

A “climbing party” up Mount Wilson near Telluride circa 1931, from Dwight’s photo album.

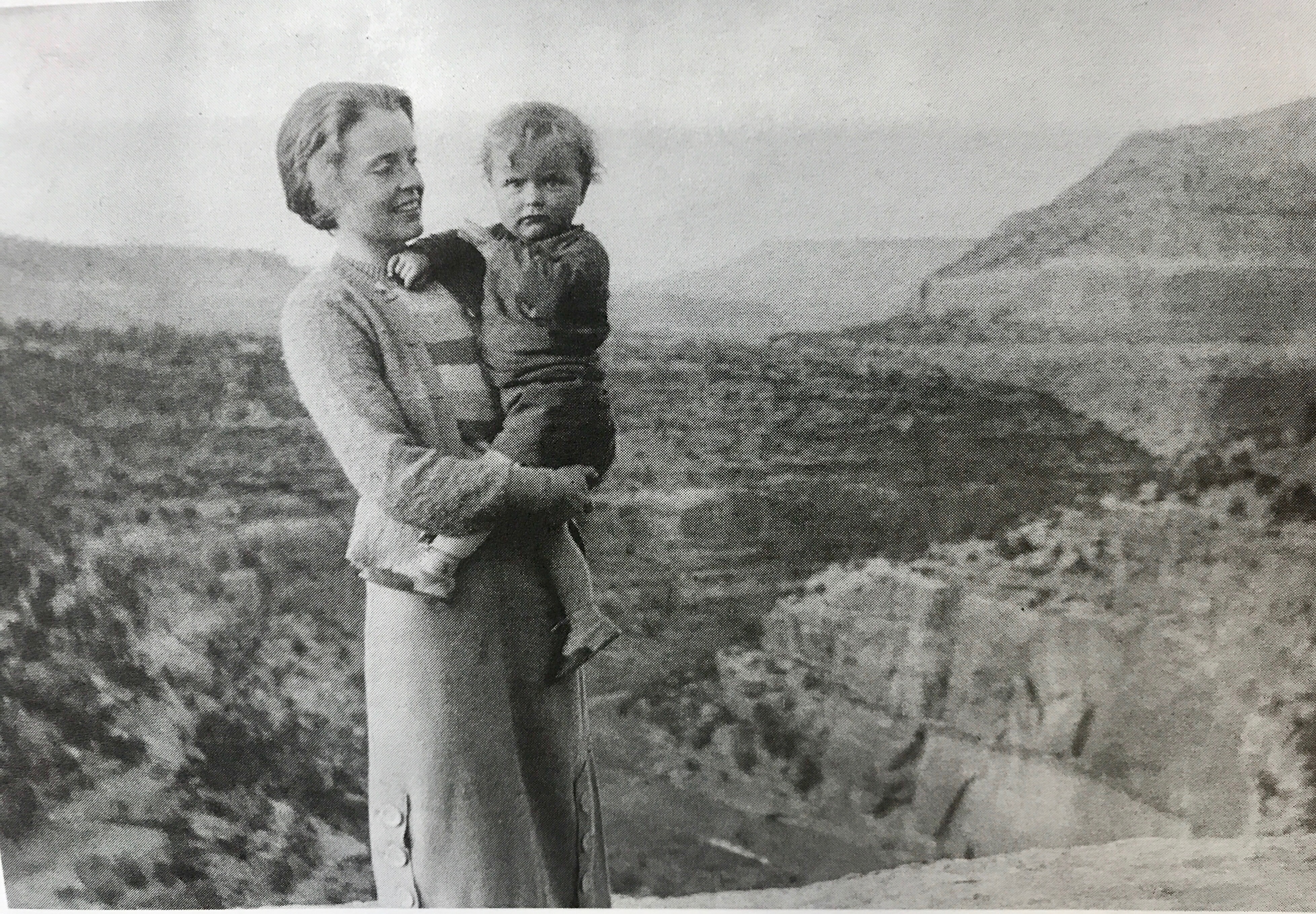

My grandmother Brookie was a high-society East Coast transplant. In the summer of 1932, at age 22, she visited southwestern Colorado for the first time, having become engaged to my grandfather that spring. A graduate of Smith College who went to UC Berkeley for graduate school, she met my grandfather in the Bay Area on a blind date when he was in his first year at Stanford Law School. (My grandfather attended law school for only that one year; he dropped out to work and save money, and he probably realized he didn’t want to become a lawyer.)

It’s amusing to think of the disapproving reaction Brookie’s mother probably had to her daughter’s desire to run off to Colorado to be with my grandfather. My dad has described his grandmother (Brookie’s mother) as “a domineering, opinionated and difficult woman. Ancestry, lineage, and ‘breeding’ meant everything to her. She was a Mayflower descendent and never let the fact be forgotten.” Brookie’s parents actually hired a private detective to investigate my grandfather’s lineage and education, since his adoption and name change from Painter to Lavender aroused their suspicions.

Brookie, engaged to my grandfather, showed up that summer to spend three months on Ed Lavender’s ranch, about 20 miles outside of Telluride in between the Lone Cone and Beaver Park. She began exploring the region with David, his brother Dwight, and Dwight’s new bride Ruth. According to her diaries (as recounted by my dad in his introduction to the new edition of my grandfather’s autobiography), Brookie loved the region and quickly learned to ride horses on the ranch, becoming quite attached to a horse named Roy. Rather than being turned off by the dirt and hard labor of ranch work, or the extreme weather and thin air of the mountains, she must have instead felt enthralled by the land and the lifestyle.

On July 18 of 1932, she and my grandfather camped overnight and made their first climb at daybreak: the 13,500-foot Dolores Peak, not far from Ed Lavender’s ranch. My father writes, “It was not a difficult climb, but it was her first ascent of a major mountain, and she was thrilled and proud.”

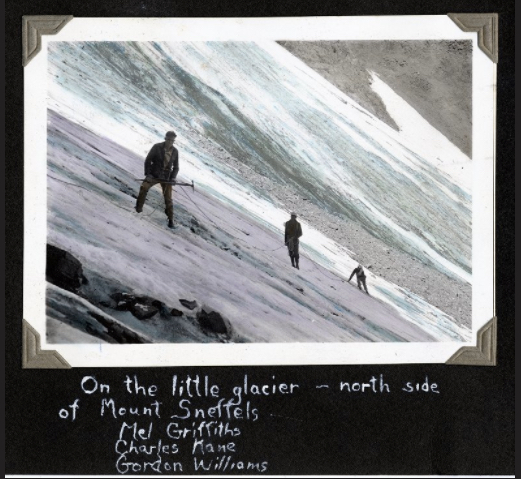

About one week later, on July 27, 1932, Brookie and David decided to take on the challenge of summitting Sneffels with Dwight. They camped the night before in Yankee Boy Basin. Swaths of ice and snow covered the north-facing route they chose, as shown in this photo from Dwight’s collection (this photo is from an earlier ascent of Sneffels, with other members of the San Juan Mountaineers).

Here’s how my grandmother Brookie describes it in her diary:

Up at 4:00 (brr). As day broke, we hiked onward and upward. Followed a trail through timber past the old Blaine Mill, by waterfalls, over streams, on to timberline. Ruth signed off there. Dave, Dwight and I went on. First over slide rock to the edge of the snow sheet, where we roped together. Dwight led, then Dave in the middle, and I at the end. They cut steps with ice axes. It took us about three hours to get up the snow sheet to rock. There it began to rain and hail. We wormed up over mammoth rocks, belaying on the rope. Above the rocks was more snow and a peak of it at the top of the couloir, where I was dispatched ahead and did a pendulum act….

Let me interrupt my grandmother’s narrative to give my dad’s explanation for what his mother meant by “a pendulum act”: “I heard many times that as they neared the summit, my mother slipped and fell fifty feet or so before the rope caught her. She said she literally saw her life flash before her eyes. Interestingly, though her diary records the climb, she makes no mention of this—unless it’s the ‘pendulum act’ noted.”

Back to my grandmother’s diary:

…Then more rocks—gigantic hunks of them. But we gained the summit!

Morgan’s photo of me scaling the “gigantic hunks” of rock my grandmother described, about 100 feet below the Sneffels summit.

Unfortunately, it was not a clear day, though we could get a considerable view, and it was such as I could scarcely comprehend—all that sweep of peaks surrounding. Despite the wintry chill, it was an experience and left an impression I’ll always have of bigness and of my own littleness.

We didn’t linger long but inscribed the record in the cairn and sped down, for storms were gathering. Quick glissading down the snow (though I’m far from adept at it)—eventually I rolled over on my stomach and dug my ice axe in. It made me rage to fail like that, but I survived. Met Ruth at timberline and we hurried back to camp to pack the car.

I was elated at having succeeded and at having had the thrill of standing up there and absorbing that stupendous view. I do love being here in this country!

The words from my grandmother’s diary, which I’ve nearly committed to memory, spoke to me as I sat on the summit and inscribed a memorial to include in the record box. Borrowing Morgan’s business card so I’d have something to write on, I wrote my name, date and, “In honor of Brookie Lavender, David S. Lavender and Dwight Lavender.” The wind blew away some tears I shed. I felt emotional because I wanted so much to thank them in person—to know them in person—because of how they’ve influenced me to get closer to these mountains, to take risks and live life more fully. I am in awe of their courage and skills.

On the summit of Mount Sneffels, paying homage to my grandparents and great-uncle at 14,150 feet.

On the way down, I worked on improving my skills of glissading down scree. Every time I slipped and fell—at one point bloodying an elbow against rock—I thought of Brookie’s words, “It made me rage to fail like that, but I survived.”

Descending Sneffels, slipping and falling along the way.

Here is the page in Dwight’s guidebook that describes their route and records my grandmother with her maiden name (“Miss Martha M. Bloom”) as part of the north face ascent (click to enlarge):

I take lessons and gain motivation from each of them—from my grandfather David, to be more scholarly; to read and write more, and also to stay connected to the land by working with my hands and savoring free time outside. I picture Grandpa operating a hoist in the darkness underground at Camp Bird. As soon as springtime came, he requested a transfer to work outside, accepting the job of busting up rocks in a rock pile. The fresh air and sublime views made the exhausting, backbreaking work bearable. Living through the Depression and working in those conditions gave him and his peers an appreciation for recreation and the beauty of the outdoors that too many of us privileged, outdoorsy types today take for granted.

From my great-uncle Dwight, I feel inspired to learn more about this region’s geography—the names of the peaks, the glossary of terms to describe their features; to break out of my running routine to hike and climb higher, pushing back a fear of heights and a sense of helplessness when faced with a seemingly insurmountable obstacle on the trail.

And from my grandmother Brookie, I gain courage to take on new challenges. To challenge society’s expectations of how a woman should behave or what a woman can do, and to risk a comfortable, easy life for the sake of following a passion.

I chase the ghosts of Dwight and Brookie because I feel a connection to them that goes beyond kinship, but I never got to meet them. I wish I could travel back in time to tag along on one of their mountain outings. I did know my grandfather David when I was growing up and remember him fondly as a grandpa, but it was only after his death in 2003, when he was 93, that I began reading his works more closely and developing a greater interest in his life as a cowboy, miner, writer, teacher and historian—and now I regret that I didn’t spend more time talking to him about his past when he was alive.

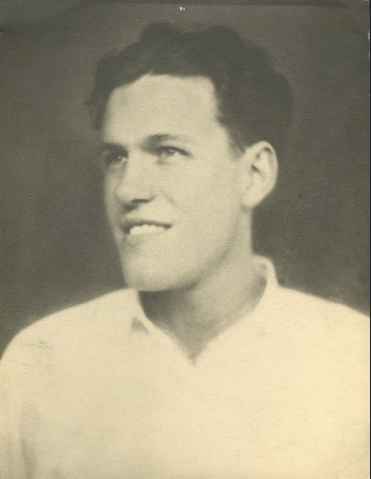

A cruelly ironic illness cut short my great-uncle Dwight’s incredible life in 1934, at age 23. Before he died, he accomplished more than 30 first ascents of peaks 13,000 feet or higher in Colorado and Wyoming, and he wrote extensively for climbing journals. When you learn he died young, you might assume he was killed by a fall or some other accident during a mountain outing. Instead, he died because he chose to do the responsible thing of returning to the classroom to earn a graduate degree in geology. When he entered Stanford University in September of 1934, he contracted the polio virus (Jonas Salk didn’t develop the polio vaccine until 1953). Within a matter of two or three days, the virus completely crippled Dwight’s exquisitely athletic body, and he succumbed to infantile paralysis.

A portrait of Dwight shortly before his death at age 23.

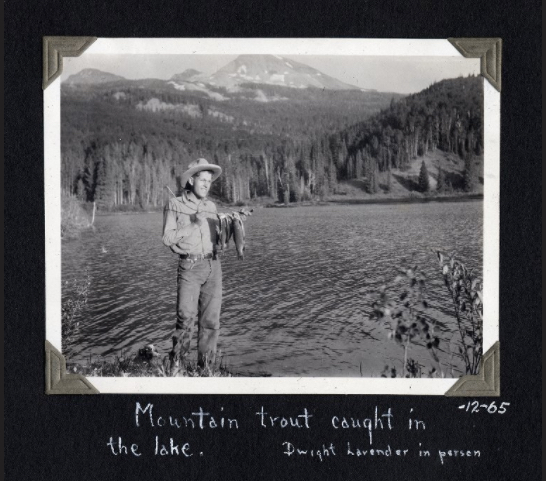

Dwight enjoying the bounty of Woods Lake.

Grieving the death of Dwight, and one year later the loss of Ed Lavender to stomach cancer, my grandfather David and grandmother Brookie worked tirelessly during the Depression. They oversaw Ed Lavender’s cattle ranch after Ed died, until the bank repossessed the bankrupt operation, which failed not from lack of effort but rather from the collapsed economy.

They headed to LA with my father, born in 1934, as a young child, and my grandfather eked out a living writing pulp fiction and articles. Eventually, in 1943, he found his calling as an English teacher at the Thacher School in Ojai, California (where I grew up and went to school), and he spent the remainder of his career living and working in Ojai. He wrote some 40 books of nonfiction and fiction about the American West during his career, twice nominated for the Pulitzer. He also rekindled an interest in running, which he developed while running track at Princeton University. I doubt he ran much as an adult (he certainly hiked a lot), but he became the longtime track coach at Thacher. Dozens of Thacher alumni have told me how they cherished him as a teacher, coach, camper and cowboy.

My grandmother, meanwhile, settled into life in Ojai and worked as the librarian at Thacher. She never had more children after my father was born, because she had a very difficult pregnancy and delivery.

My grandmother Brookie with my one-year-old dad in 1935.

A snapshot of a framed photo of my grandparents, from 1952, hanging in the Thacher School library.

One day in 1959, when Brookie was 49 years old (one year older than I am now), she suddenly collapsed on the Thacher campus and died of a brain aneurysm. Her sudden death floors me—one day, no warning. I wish so much I could have known her. Instead, I learn what I can about their lives back then.

Mostly, they remind me to live life with a keen awareness of mortality, because you never know which day may be your last; to appreciate your loved ones, make the most of your time together and pursue your “someday” goals sooner rather than later.

Their history doesn’t feel so distant when I’m able to retrace their steps and re-read their writing. Learning about their relatively fleeting lives that passed through these massive, eternal mountains makes me want to leave behind stories for my future grandkids.

One day soon I hope to go to the University of Colorado at Boulder and delve into the special collections, where my great-uncle and grandfather’s works are kept. Thankfully, three of Dwight’s photo albums are available for browsing online here. And if this post has sparked interest in my grandfather, I invite you to read his obituary here and encourage you to read some of his books, such as One Man’s West, Bent’s Fort and The Way to the Western Sea.

Someday soon, also, I hope to go to the La Plata mountain range, 15 miles northwest of Durango, and climb the 13,160-foot peak named Lavender Peak in honor of Dwight. Time is always running out.

Dwight in his element. Take time to look around!

Wow! What an extraordinary story and so well written and told, Sarah. Thanks for sharing this personal story and journey.

Wonderful legacy <3

I echo Carolyn’s sentiments. What an incredible multigenerational story and a great reminder to seize the day. Thank you for sharing your story, Sarah. I look forward to reading your story of summiting Lavender Peak when the time comes.

That was wonderful!!! Thank you so much for sharing about your family, I feel like I would have enjoyed their company!! People back in the day seemed to be made of tougher stuff.

Wonderful. Thank you for this.

Beautiful piece, Sarah! The historic photos are amazing as well. When I climbed Sneffels a couple summers ago, I was so excited as we went up Lavender Col and I knew it had been named in honor of your family.

Like your grandmother, I summited on a day that wasn’t particularly clear, but it still gave me such an unbelievable sense of appreciation for the bigness of the landscape and my own wonderful insignificance among it.

Any chance of this getting spun into a long-form print piece? 😀

This is really cool. Great legacy.

This is great, been following you a long-time and found this very interesting. Incredible that you can know this much detail about personal history.

Thanks, Steve! Actually this blog post just scratches the surface … it could have been more detailed, but I feel this was long enough :-).

Your grandparents live in you! I loved reading this. Thank you.

What a great article Sarah…must be so rewarding to research. I’m traveling from Brooklyn next month to run the Bear 100 and my family has a lot of history in the Logan/Bear Lake area. This inspires me to delve further into my own family’s past and do some exploring before the race. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks John, and good luck at The Bear!

I was mesmerized by this, Sarah. What a wonderful tribute. And you obviously inherited your grandfather’s way with words, and grandmother’s spirit and love of the mountains. Thank you!

One of the best posts I’ve read. Right from the start unbelievably captivating. I’m curious what they would have taken for energy while they were climbing. And the extra weight of everything compared to today. Thanks for sharing this.

Wonderful. Great writing and story, but of course, it’s not a story, it’s your history, your family. Perhaps worthy of a screenplay even! Can’t wait to hear about your summit of Mt. Lavender. I have a beautiful photo of Mt. Sneffels I see every day and now I know how it feels to summit. What an amazing part of the world. Thank you for sharing.