The Wasatch Front 100-Mile Endurance Run is as hard as Colorado’s Hardrock, according to some who’ve run both.

It’s a classic, in its 36th year.

It’s got over 25,000 feet of elevation gain and about as much descent.

It gets really hot during the day, and really cold at an elevation of over 10,000 feet in the middle of the night.

It’s got sections nicknamed Chinscraper, Lungsucker, Puke Hill and Grunt; “ball-bearing-size loose rocks,” “wet boggy areas,” “very heavy brush” and “excruciatingly steep” descents, according to the course description.

And I learned these facts when?

The day before I joined 312 other starters at the 5 a.m. start north of Salt Lake City, in the East Mountain Wilderness Park.

Most people who attempt Wasatch make training for it their summertime focus. They log back-to-back long runs on mountainous terrain and sweat the details of their race plan. I was not one of those people.

I spent the summer focused on other things involving family and work, downplaying the challenge of Wasatch because I wasn’t running it competitively; I just wanted to finish, so that I’d get a qualifier to enter the Hardrock 100 lottery. I thought I could handle the challenge because I hiked and ran a good amount in July while at high altitude in Colorado. In August, my training was not too shabby—if I were training for a 50-miler. Weekly mileage hovered around 50 – 60 and topped out at 74 on the best week. I ran a 50K, a nighttime 20-miler and walked around more during the day.

Then, during the two-week taper before Wasatch, I got a lousy head cold and felt exhausted from the stress of transitioning my two teens to their school while meeting some deadlines and making a major decision with my husband that involves a property purchase. I drank beer and ate entire bags of evil Bark Thins, then freaked out that I was five pounds heavier than when I ran a 100-miler the prior year. I visualized myself running Wasatch with the Yellow Pages strapped to my butt, since that’s about the equivalent extra poundage.

Like an unhealthy doctor, I was a coach who wasn’t following my own advice (as detailed in how to prepare for a successful 100-miler) to train and study the course. The race ranked on my to-do list next to getting the van serviced. I just couldn’t get my head around it and couldn’t care enough. Until I was there.

Killing time at the pre-race meeting the day before the race, laptop open to cram some studying of the maps, the chatter of those around made me belatedly wake up to the fact that this is a really special, really hard event.

Errol “The Rocket” Jones—the pioneering ultrarunner I frequently spot running in the Oakland Hills—sat down nearby and started greeting other old-timers like veterans who reunite a quarter-century after battle.

“Rocket, I don’t know if I’m up for this,” I let on.

“Sarah, remember this: It’ll be fun, until it’s not, and then it’ll be fun again.” Then he laughed and laughed, recognizing the truth and absurdity of his statement.

“The Rocket” far right with “Wasatch Fred” Riemer (left) and Paul Alsop (center). The three have more Wasatch finishes between them, and stints as pacers and aid station volunteers, than I can keep track of.

Another older gentleman proudly showed me his Wasatch 100 brochure from 1985.

“There is no tougher hundred miler in the country…” it said.

I simultaneously thought, “Oh, shit” and “how cool!”

I neglected to mention the one thing I did right and smart to prepare, so I wasn’t totally screwed: I recruited a dream team to crew and pace me, my old friend Jennifer O’Connor and her husband Chris. They have run lots of ultras, and they are pros as crew. I took comfort in the fact they would take care of me and I wouldn’t have to worry about them. They’d meet me first at around Mile 39, then take turns pacing me from 52 to 75 and 75 to the finish. Thank god. I didn’t have faith in myself, but I had faith in Jenn and Chris. Plus, the fact that I had to meet them forced me to do a minimal amount of planning with regard to pacing and organizing the stuff I’d need.

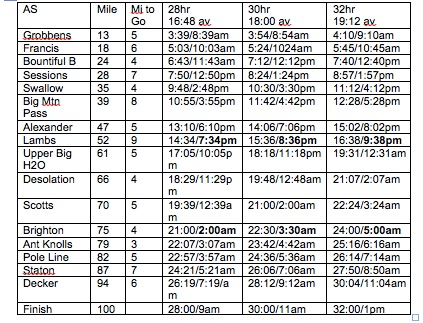

I made a pace chart for Jenn, Chris and myself that showed what I thought were conservative finish times: 28, 30 and 32 hours. I thought I should run sub-28. I surely wanted to finish sub-30. I included the 32-hour pace times so I’d know if I were going really slowly but still getting by, like mustering a C. The race has a 36-hour cutoff, but I couldn’t imagine being out there for 36 unless I took a long nap midway.

I kept this little chart in my pocket, to pull out and measure the degree to which I was rocking or sucking over the miles.

I also got a temporary tattoo at the pre-race meeting. Having this chart, which shows the aid station locations as well as the elevation profile, proved extremely helpful.

I woke up at 3 a.m. and Jenn drove me to the start a little after 4. It still hadn’t really sunk in what I was doing.

Even after the start, ambling along on the first five easy miles, I didn’t grasp the enormity of what lay ahead. I didn’t feel nervous—I didn’t really feel anything.

At the first big climb, I felt a tad impatient, because we were forced to hike in a slow conga line due to the narrowness and grade of the trail. I didn’t try to pass anyone; I just chilled out and told myself that the slow start was for my own good. Beside, it’s not like I could have really run it—I just wanted to hike faster and have fewer people around me. The first climb, from mile 5 to 9.5, goes up about 4000 feet and summits on Chinscraper.

Some runners scrambling up Chinscraper, around mile 9.5 and about 9500 feet elevation. I didn’t have too hard a time with this; I used my hands when necessary and enjoyed the climb. Photo by Lane Bird via Facebook.

The first quarter of the race was pretty uneventful. There’s a long, smooth downhill dirt road going into the Mile 18 aid station that I ran hard but not too hard. My body felt fine, and I was enjoying the mid-morning temperatures and views. So far, so good.

I deliberately saved my iPod for the second quarter of the course, miles 24 – 52. I don’t like wearing music during the early miles when trying to relax and when the trail is crowded. I also don’t like music in my ears when I have a pacer. So those second-quarter miles felt turbo-charged with good tunes, which helped me through nasty stretches like Sessions (Mile 28) to Swallow Rocks (35). “Tough session, hard to swallow” was my mnemonic device for remembering that would be a hard part.

The course description states antiseptically, “In this section there are frequent rocky areas with loose rocks to negotiate.” Um, yeah! In one part, we descended from an elevation of 9000 to 8000 feet on a trail with the slope and width of a playground slide, covered with tennis-ball-sized rolling rocks—but it was hard to see those ankle-turners, because the sagebrush was so overgrown that my eyes tended to focus on the branches that scraped and poked my thighs, which looked as scratched-up as if attacked by a cat.

Even harder were the miles between about 42 – 47. I’m a better climber than descender, and these downhills tried to eat me up! “The trail becomes difficult as you run on ball-bearing size loose rocks,” the course description intones. “Exposure to the sun may become severe with temperatures sometimes above 100 F. The hot sun reflects off the light-colored soil …. Dehydration strikes hard. Nausea runs rampant.” Yep, it got toasty.

But, unlike many runners nearby who cursed the trail and wilted in the midday direct sun, I managed to stay in a peppy mood because I had given my kids free rein to load my iPod with funk and hip hop. I passed the miles listening to their songs, such as Jay Z & Linkin Park’s Encore, Macklemore’s new single Downtown, GRIZ & Big Gigantic Good Times Roll, and of course Uptown Funk.

I was doing AWESOME (as many people at aid stations told me) in the first half — just a tad under 28-hour pace, which felt nice and manageable. As I may have mentioned, I was pretty well-trained for a 50-miler!

I took care of my body and ate regularly. Boiled potatoes with salt, and a half a banana smeared with Skippy, were my go-to snacks at aid stations. I also drank well, chugging Sprite at aid stations and Rocktane from my bottles and hydration pack.

I was quite happy with my hydration setup: an Ultimate Direction Ultra Vesta with the two 10-oz bottles in the front and an optional hydration bladder in back, filled only halfway as a reserve source. I also had UD’s Fastdraw 10 handheld, which I loved, because it felt like just the right size and I used its little pocket. I never worried about running out of liquid, but I also didn’t feel too weighed down.

One question crossed my mind, however: Since I’m eating and drinking so much, why isn’t anything coming out the other end? My body felt like a holding tank for liquids and solids, and I started to develop the puffiness that often hits me in ultras with high heat.

I grabbed these next few pics off of Facebook, even though I don’t know where exactly they’re taken (and apologies I don’t know the identity of most runners pictured), because these photos typify much of the terrain that we traversed during the day.

We ran through innumerable pretty aspen groves, like this one, which was a relief from the direct sun! This is of runner Wendy Clark by Matt Clark.

It was a joy to meet Jennifer at the busy Lambs Canyon aid station, next to a freeway underpass. It was about 7:30 at night. I changed into a fresh shirt, put on a jacket and headlamp, ate a small bean-and-cheese burrito and drank a carton of vanilla milk (I love sugary milk late in an ultra).

Thus began the second half of Wasatch, and like a tale of two ultras, it was the best of times, the worst of times…. It was a joy to spend hours with Jennifer, getting caught up on all the things we haven’t had time to talk about recently. (She and I have been friends since the early ’90s, and she got me into running in 1994.) She—and later, Chris—both were exactly the kind of pacers I needed: encouraging and patient, not pushing.

Jennifer told me an adage years ago that always proves to be true. To paraphrase: “The things you think will be problems in ultras usually turn out not to be. It’ll be something else.” Going into Wasatch, I was worried about my achy toes, concerned I might have the start of a stress fracture or neuroma. But my feet felt fine and dandy—no pain at the base of the toes, no bad blisters.

Everything from my feet up, however, became a problem.

I began to suffer an all-over stiffness and lightheadedness, aggravated by getting chilled to the bone and being at high altitude. I paused too long at the Mile 61 aid station and got cold to the point I had chattery teeth and twitchy muscles. I tried to speed up to warm up, but any effort to go faster sent my heart rate into the stratosphere. So I plugged along, hiking but still trying to run most flat and downhill sections.

A mental fog rolled in. I began to think I was in a time machine in which I aged a year with each mile, and the miles mirrored my imaginary age, so as we approached 70 I was morphing into an arthritic septuagenarian who needed to nap a lot.

Jennifer also proved to be right when she told me, back at the Lambs Canyon aid station, that I’d start peeing once my core body temp went down. After sunset, I had to relieve myself with increasing frequency, as if my body wanted to void itself of anything extra in it. This felt good, until it didn’t. I lost countless minutes ducking into the dark bushes, squatting, and then returning to the trail even more stiff and clumsy. More and more runners passed us.

Meanwhile we kept climbing, climbing, climbing up to a point around 10,000 feet at mile 70 called Scott’s Peak. It was hard, but the following five miles that went back down 1000 feet to the Brighton Lodge Aid Station were harder. The overriding feeling I recall from these miles is frustration, because I felt so slow and uncoordinated. We popped out of the trail onto a regular paved road for a few miles, by Brighton Ski Resort (near Park City), and I tried to revive the runner in me to take advantage of the smooth road—but still I sucked, unable to shift out of grandma gear to start running.

The time was around 4:30 a.m., and we were approaching the big aid station in a ski lodge where we’d meet Chris and he would take over pacer duties. Wasatch veterans had warned me to “get the hell out of Brighton” because the aid station can take so much time if you let it—but I knew I would need time to revive.

When we entered the crowded, steaming lodge, I made a beeline for the bathroom and passed eternity or at least 10 minutes in the calm, clean retreat of the bathroom stall. I never let myself sit at aid stations (“beware the chair”), so this toilet seat offered a respite I lacked all day. I hunched over, resting my arms on my knees, my head on my arms, my eyes closed, and I thought about how I take “power naps” at home in five minutes and that’s maybe what I was doing then and there, but I had to stay awake enough so I wouldn’t slump forward all the way and fall off the toilet.

Get the hell out of Brighton—the warning bell tried to clang in the fog of my brain. I forced myself out of the bathroom and reunited with Jenn and Chris, who thankfully acted businesslike and efficient. I could not have handled looks of pity at that point—I just needed them to tell me what to do, and they did. The only mistake they made was offering me a serving of hash browns that the aid station was cooking for breakfast, and when I caught a whiff of that greasy hockey puck of potatoes, I felt a wave of nausea and lost any desire to eat anything.

Meanwhile I was thinking, I can’t believe it’s breakfast time! It’s so f**’ing late! I should have been in and out of here before 3 a.m., not 5.

My friend Howie Stern, who was pacing someone else, passed by. He’s done Hardrock several times as well as Wasatch and thinks Wasatch is harder. (No way! I had told him at the pre-race meeting a lifetime ago.) I must have looked at Howie like a ghost or refugee with shell-shocked eyes, because he told me later, “When I saw you at Brighton, the reality of the day was as clear as a bell in your eyes. … I hope to never see that look in your eyes again.”

I had been ambivalent about whether to start using trekking poles at Brighton, to get up and over the course’s highest and hardest pass. “Take the poles,” Howie told me. OK, I trusted him. I got out my Black Diamond Z poles—which I use only when pacing at Hardrock—and told Chris we had to get out of there.

We were at mile 75, and I felt 75. I left the aid station feeling more weak and disoriented than when I entered, which surely couldn’t be good. But Chris was a champ and got me out the door.

Jenn took this photo of Chris and me heading out of Brighton Aid Station just after 5 a.m., facing the final one-fourth of the course. I was not a happy camper.

I had no idea what we were in for; I only knew we had to climb about 2000 feet in 2.5 miles, in the deep darkness just before daybreak. I would discover that those miles feature rock outcroppings that stand in the way of any straightforward movement, so the hiking becomes more side-to-side and up-and-down than forward. At times, I had to reach my arms all the way up to plant a pole several feet higher, lodging it in some rock crevice, and gain enough leverage to pull myself up. Then I would pause and catch my breath.

Our pace slowed to probably a 45-minute mile—step, pause to catch breath, survey the rocks, plan another step—and with each pause, I felt myself totter or lean and wobble, eyelids drooping. Objectively I knew I was on the verge of passing out. I could tip over and go to sleep, which would bring immediate relief but, unfortunately, would probably cause me to tumble down several hundred feet and freeze. Objectively I also could tell that Chris was worried about me, and at one point he moved his arms quickly as if to catch me, but he kept his cool and his “one foot in front of the other, let’s do this” attitude. Objectively I knew I had a case of The Stupids—of disorientation and poor judgment—taking over my brain, and deep down this frightened me. I wondered, Rocket, when is it gonna get fun again?

It helped to keep flashing back to my experience of pacing Betsy Nye at Hardrock in 2014. She had come into the aid station hours late, like I did at Brighton, and she and I ascended the 14’er Handies Peak in the dark at a similar glacial pace. I had witnessed her struggle, and I hung onto the memory that she had made it to the summit—that one foot in front of the other, no matter how slow, still spells progress—and that the sun would come up and I would make it, too.

If the sun had been up, I’m sure we would have appreciated the views. This photo shows the area around Catherine’s Pass, taken by Cory Reese who, unlike I, carried a camera and took great pics (read his wonderful race recap here).

Daylight broke just after the elevation high point at mile 77. Chris and I picked our way carefully down the precipitous trail, negotiating one rock at a time, and I felt profound gratitude for my trekking poles, which kept me from face-planting. When I looked up at the soft, golden glow reflected on aspen trees and towering rocks, I had to admit it was pretty, but I also didn’t really care.

We made it to the Mile 79 aid station, called Ant Knolls, which was possibly the coolest aid station ever, like a bit of Burning Man in the woods. It featured a giant metal dome with lots of lights. Volunteers fried up breakfast. I don’t remember if I ate anything. I just kept gulping ginger ale.

The Ants Knoll Aid Station seen at night, complete with a red carpet at the entranceway. Photo by Emina Alibegouic via Facebook.

You’re supposed to feel better after the sun comes up in a 100-miler, and I thought I would. But as we headed out of Ants Knoll and up a sadistic half-mile, 500-foot hill called The Grunt, I flirted with desperation. We had 20 miles to go, and I was taking more than a half hour per mile. I was so ridiculously, painfully, helplessly slow that I might end up chasing the cutoffs for the 36-hour pace. The prospect of being out there all morning and all afternoon, for the sake of virtually crawling 20 miles, was more than my 80-year-old, doddering and senile self could handle. I was supposed to be DONE by 9 a.m., or 11 a.m. at the latest.

That’s when I thought about quitting—but only for a moment. I kept repeating, “A DNF hurts more.”

Instead of thinking about the full distance left to the finish, I concentrated on the prospect of meeting Jennifer at around Mile 90, when I could ditch my jacket and freshen up. Chris and I transitioned from the trail to a fire road that just went on and on and on. It’s too boring and ceaseless to describe.

I wasn’t so sleepy by that point, thank goodness, but I still had The Stupids and moved inefficiently. At one point I tried to open a Gu packet; it exploded on my hands, so I tried to lick it off, and then I wandered off to a puddle to kneel down and wash my hands, and then I could barely stand up—that’s how the morning went, with everything taking extra time to accomplish. I don’t know how Chris maintained his patience, but I appreciated that he did.

What sucked most about this fire road was its lack of shade. The sun came up and reflected on the light-colored sand, and I felt my skin start to crisp like toast.

Finally we got to Jennifer. Here is one of several less-than-attractive photos she took of me, which captures the dust and dryness of that dang road:

She gave me a hug, and that’s the only time I got tears in my eyes and almost broke down. I felt so broken, but I had to keep myself together.

For the final 10 miles, I developed a mantra of “Suck It Up and Get It Done.” I started a walk-run pattern of briskly walking a minute, running a minute. I regained some strength and flexibility in my leaden legs, and Chris and I became motivated to get in before 2 p.m., under 33 hours.

Seeing Jennifer that last time, and feeling that surge of emotion, marked the climax of my race. After that, I felt flat-lined emotionally, motivated only to be done and to try to finish before 2 p.m. These final miles, all open fire road, really are hideous because they’re so bland. The fast finishers run them in the coolness and dark. Us middle- and back-of-the-packers run them in blinding brightness and 90-degree heat, dehydrated and desperate to be done. I developed a deeper appreciation for all finishers toward the back of the pack, because the challenge feels exponentially harder with each passing hour on Day 2. Each time I found it within myself to run a stretch of the road, I felt a flicker of pride.

As a final insult, the last mile of Wasatch traversed asphalt, and heat waves visibly radiated off the surface. I thought to myself, What is this, Badwater??

The ending was totally anticlimactic, so much so that it was funny. I crossed the finish line in 32:38, and few people besides Jenn and Chris and my friend Helen (who finished 3rd, hours earlier) seemed to notice or care.

We were so much later than planned that we had to hit the road quickly. I crawled into the back seat of Jennifer and Chris’s car and passed out immediately. About a half hour later, I woke up disoriented.

“Why are we still driving?” I asked.

“Sarah, you ran 100 miles—it’s really far,” said Jennifer.

I never had any sense of the geographic scope or location of this race, stupid me, until I found myself in the middle of it.

Back at the motel room, I was too dirty to rest on the furniture, so I lay on the floor instead.

They looked bad–but actually felt OK. The blackness is only dirt, not rot. The tape prevented blisters. Nice work, feet, you got the job done!

About a third (110) of the 313 who started the 2015 Wasatch Front 100-Mile Endurance Run dropped out, but I was not among them. I felt deeply satisfied that I sucked it up and got it done.

Nice work, Sarah! The Rcoket knows his stuff (and did you notice that he’s always surrounded by attractive women?)

As for Wasatch: was that fun or what?!?

Excellent writing and photos Sarah. Enjoyed reading your journey. Congratulations, well done on your accomplishment!!

Congratulations! Where does one get such custom temporary tattoos? That is brilliant!

I’m not sure; they were handed out at the pre-race meeting.I’ve seen them at other ultras, too.

You’re one tough cookie, Sarah. Keeping going when it feels impossible is the hardest – but most rewarding – thing about this crazy sport. And now Chris and I fell in love with Wasatch and can’t wait to try it ourselves!

Great stuff! I have really enjoyed your writing lately. Insightful and motivating.

Wow, well done and run! You are amazing!!

Fantastic run and report! When facing fierce realities, all we can do is put one foot in front of another. You did just that, and in style! Great photos, bring back memories. Strong run, Sarah.

This brought back some all too familiar memories from my Wasatch. Some good, some bad. Thanks for such a real write-up.

Sarah, I love you put the true struggles of mentally pushing beyond the pain and being happy with the time you finish. (Because we all can’t PR every race.) Great writing!

Congratulations, Sarah!! Sounds like one of those finishes that brings a great amount of pride, not a lot of glory. I think we need those sometimes to remind us how hard this sport really is, and to remind us what we’re made of. Which in your case is some tough ass stuff!

If all your 100 milers went as smoothly as the first you finished, and you were as mentally or physically prepared, I wouldn’t be able to take you as seriously. Way to suck it up and get it done!

Congrats on your finish! One thing I will say in regards to Wasatch vs Hardrock…you cannot compare the two. I have finished Wasatch and was an observer at Hardrock this year. Although Hardrock has a longer time limit the altitude, weather, exposure, creek crossings are way more intimidating than Wasatch. Not to mention the course is intentionally not marked very well. Just mho…

Jay, I agree. I think HR would be tougher any year due to the severity of the weather and altitude. I was surprised that some people think Wasatch is as hard in its own way. It’s a bit of an apples and oranges comparison and certainly subjective. Some may think Wasatch is harder insofar as it has more runnable stretches, so you have to do more real running to be competitive. One thing for sure, they’re both hard!

Congratulations on toughing it out and getting that finish!

I’m training for the Addo Elephant 100 miler and your blog is a treasure trove of inspiration and useful info.

Thanks!