This guest post is written by Jeff Kozak, an accomplished ultrarunner whom I got to know last winter. His story ostensibly is a race report on the Pine to Palm 100 Mile Endurance Run in the Siskiyou Mountains of Southern Oregon. But it goes beyond the race itself to capture the profound physical and mental odyssey of struggling to master an endurance event.

This guest post is written by Jeff Kozak, an accomplished ultrarunner whom I got to know last winter. His story ostensibly is a race report on the Pine to Palm 100 Mile Endurance Run in the Siskiyou Mountains of Southern Oregon. But it goes beyond the race itself to capture the profound physical and mental odyssey of struggling to master an endurance event.

Jeff, who’s 37, has been running ultras since 1997 and playing in the mountains, primarily the Sierra Nevada, since he was 5. He considers himself a 50K and 50M “racer” but so far a hundred-mile “finisher.” He finished five 100-milers prior to Pine to Palm. His 50M PR is 6:51 at the 2009 American River 50, but he says his hands-down best ultra performance is his 7:06 course record run at the 2009 High Sierra 50M. He lives in the Eastern Sierra town of Bishop and works at the outdoor and mountain running specialty shop Sage to Summit.

The Prologue

At 4:45 a.m. on Saturday, September 17, I bolted upright in my tent to the sound of the alarm clock. I smiled. This NEVER happens. Sleep the night before a race is usually as elusive as my 14-year-long quest for what Tim Twietmeyer has referred to as the “Holy Grail of 100s,” the race where it all comes together. It is often replaced by anxiously staring into the black void of night contemplating the quantity and, more importantly, quality of training that got me, one more hard-earned time, to this finely tuned moment separating the mundane from the mystical as only 100 miles of voluntary, self-propelled motion through the mountains can.

Am I over-trained? Under-trained? Did I run long enough? Frequently enough? Fast enough? Was my taper too long? Too short? Am I carbo-loaded? Carbo-bloated? Do my racing shorts make my ass look fat?

These questions are largely philosophical, an athlete’s existentialism. There are no absolute answers. And the mind would never fully, contentedly accept any combination of training data fed to it anyway. To borrow a line from a 1990’s Kevin Setnes’ Ultrarunning mag column, we are all an “experiment of one.” We like to deny it, seek shelter in the herd mentality of our species, but it doesn’t change the reality. It is true of life and so it goes with ultrarunning. The doubt-filled questions will always be there, with a multiplicity of “answers” dangling from the infinite thread of our collective thought processes like a strand of recombinant DNA.

Nevertheless, HAD I been awake, squirming in my sleeping bag all night, I would have been reflecting on what I considered to be one of the best buildups I’d ever survived intact in preparation for a hundred-mile-long breakdown. The words “survive” and “breakdown” may seem like odd choices but they are definitely appropriate.

Arriving at the starting line animalistically fit AND healthy, with no nagging injuries, is a minor miracle unto itself and a crucial prerequisite for a chance at success, a success that comes at an ironic price. And the price is precisely this: the chance to stand at Mile Zero in the best shape of your life and release the pent-up potential energy of your training in a controlled manner, calculated to (hopefully) get you to Mile 100 at exactly the time you are, in some ways, in the worst shape of your life.

Like a geneticist in a lab (with a sweet view), my summer-long experiment for Pine to Palm (P2P), running on Sierra Nevada single-track and Owens Valley dirt roads, had involved some recombining of training and fueling principles in the hopes that the newly evolved form would be better adapted to the task at hand: survival; not stumbling-across-the-finish-line survival, but survival in style. I haven’t DNF’ed since my first two hundred-mile attempts at Angeles Crest in ’98 and ’99, but I haven’t had the competitive success I believe I’m capable of, either. Without exception, somewhere in the twilight zone of the final 30 miles that Andy Jones-Wilkins slyly refers to as the “miles that make hundreds special,” the crucible of competition reduces me to a crawl.

In a classic snapshot of mid-’80s ultra-distance trail running, the documentary about Western States titled Desperate Dreams, multiple-time winner Jim King classifies three species of hundred-milers: the racers, the runners and the survivors.

Brewing up and savoring a steaming cup of coffee, more out of pre-race ritual than anything as I was refreshingly wide awake due to the surprisingly solid snooze, I felt confident that I was standing on the precipice of a new level of performance. I was tired of being ground into a survivor by the mortar and pestle of this sport. I wanted to at least be a runner, if not a racer, until the end.

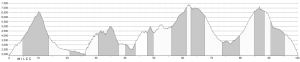

The Pine to Palm 100 course profile. The lowest elevation is 2000 feet, and the highest is almost 7500. The gray and white vertical stripes indicate the distance between aid stations. Click for a downloadable PDF version.

The Racer

The Pine to Palm course is a point-to-point traverse of the Siskiyou Mountains of Southern Oregon, starting just outside of the tiny community of Williams and ending in downtown Ashland. The course has one moderate and three “epic” climbs, totaling 20,000+ feet of ascent. The first “epic,” ascending the northeast shoulder of 7000-foot Grayback Mountain, starts immediately.

With only the faintest hint of dawn in the eastern sky, 75 intrepid and eager souls took the first steps toward chasing their individualized dreams and facing down their personalized demons. I settled into the back end of a secondary group somewhere in the top 10, comfortably slower than the torrid pace already being set by the leaders, which included last year’s winner Timothy Olson, Yassine Diboun and Chris Downie, three guys I had no illusions of being able to run with.

My race plan was very simple: Keep the faith in what had worked fabulously well for me in my long training runs, and forget about everyone else. Either people would come back to me throughout the day or they wouldn’t. All I wanted was a solid performance from start to finish and let the places fall where they may. There is absolutely nothing profound or revolutionary in that statement; in a race this long everyone, more or less has to—or is eventually forced to—anyway.

Nevertheless, it is amazing how easy it can be to lose sight of that elemental truth and get caught up trying to follow someone else’s protocol. Experiment of one, remember? Mess around with another’s, especially a more accomplished one’s, equipment and methodologies on thesis defense day, and you’re bound to blow up your lab.

One major change I had made in training was my fueling strategy; more specifically the FREQUENCY of my fueling. After many years of stubbornness, I had finally digested the fact that I needed to consume significantly more calories than I really wanted to. On my 8- to 16-hour long runs in the Sierra, I began forcing myself to eat something in the 100 to 125 calorie range every 30 minutes.

On race day this meant slowing to a walk when I otherwise probably wouldn’t, either because the terrain was easy or downhill, I was feeling great, or I was gaining ground on someone, or some combination of the above. Every 30 minutes. No exceptions.

Ascending the single-track snaking its way up the thickly forested slopes of Grayback Mountain as the sun rose, casting a golden hue on this arrestingly beautiful arc of the globe, was easily the first of many emotional high points of the race. For the most part, the trail was soft and smooth, a refreshing change from the granite-ridden, mule-stepped rough trails of my beloved spiritual range, the Sierra. Perfect for running. Easy to get into a rhythm. At 10 miles and over 4500 feet of gain, this climb was not short; but it was sweet, and it went by effortlessly. I almost didn’t want it to end.

Several miles of singletrack descent brought us to a long section of dirt road that continued the drop down to the Applegate Valley and the Seattle Bar aid station perched above the bathtub ring of a significantly drawn-down Applegate Reservoir. This road section was FAST, and another major change to my training came into play: speedwork.

I have rarely done speedwork since getting into ultra-distance trail running in 1997. I logged so many lung-bursting miles as a prep and collegiate runner I simply found it way too easy to choose a slow mountain run in a beautiful setting over intervals every time the thought occurred to me that the plateau of my performance would be significantly lower in elevation without them. The one time I did regular speedwork as an ultrarunner, in preparation for the 2009 High Sierra 50 Mile, I was rewarded with a breakthrough race at that distance, and a course record. But old habits die hard, and there are so many trails to explore. Soon enough, interval training shorthand was again nowhere to be found in my journal.

This summer, I revisited the anaerobic arena of half-mile and mile repeats. The adaptation was arduous, but eventually I began noticing the twin effects of increased leg turnover and elevated lactate threshold. Cruising down the road to Seattle Bar, rattling off mile after sub-8 mile with a mellow heart rate, I reveled in this. Keeping the horses reigned in became the primary concern. I felt like I could be going much faster, but it was way too early to be running hard, despite the seeming urging of the terrain.

I cruised into Seattle Bar at mile 27 in 4:45 feeling relaxed and in total control. My friend and aid station captain, Craig Thornley, was there with a full compliment of good-natured ribbing to keep the mood light as I quickly switched out my bottles and waist pack. Within minutes I was on the trail to Stein Butte.

On a course that is predominantly dirt road, this section was another piece of trail running paradise. Enjoying the sweeping views along the undulating ridgeline of the first 30 miles already covered and the next 20 miles to come, where the trail popped out into open grasslands and the welcoming coolness where it dipped back into the predominant tree cover, I was startled out of my solo reverie by the first runner I had seen in hours.

The first two runners were long gone, and I wouldn’t see any others until the dirt road climb out of Glade Creek after mile 74, not including Yassine Diboun, whom I passed and talked to just before he hobbled into the Hanley Gap aid station at mile 48 using two tree branches as crutches due to a ruptured plantar fascia. It is never fun to pass someone in this manner. In a weird way it bothered me. Here was a guy who was probably hours ahead of me before disaster struck, and now I was moving up a place because of his misfortune. Injuries are a part of the game, but it doesn’t mean they don’t suck.

The flat two-mile loop around Squaw Lake at mile 38 gave me another surge of confidence. It was an opportunity to open up the throttle a bit and take stock of the situation. I was firing on all cylinders.

On the out-and-back up to Squaw Peak at Mile 48, I moved into third place, made short work of the rolling stretch to Squaw Creek Gap at Mile 56, and began the long gradual dirt road climb up to Dutchman Peak. My iPod blasted forth a steady stream of sonic energy, and I felt a chill run up my spine accompanied by goosebumps. The plan was working. I felt the power. It carried me effortlessly up Dutchman Peak, and as the rapidly lowering sun cast a surreal glow on the alpine Siskiyou Crest, with Mt. Shasta standing alone, tall and proud on the southern skyline as a volcanic temple erected to the changes wrought by the passing of time, I wanted this moment to last forever; at the very least to permanently etch itself in my mind, regardless of this particular race’s outcome, as a testament to why we do these things. Witnessing the same exact scene but having driven to it, while still beautiful, is not a similar experience. Not even close. Your state of mind sets the stage for what you perceive, and you can’t fake a 62-mile feeling. You have to earn it.

Dropping in on the aid station at Mile 63 where my pacer and friend of 25 years, Dave, awaited, I saw the next two runners coming up to the junction for the peak. I couldn’t help but note that I had a solid 10 to 15 minutes on them, but that really didn’t matter. What mattered was what I was feeling. And I had never felt like this, this far into a hundred. I hadn’t even had so much as a lull in my energy or a gurgle in my stomach or a twinge in a muscle.

On the long descent into Glade Creek at 74 miles, darkness draped itself over the landscape, and our world was quickly reduced to the soft spectral glow of our headlamps. Admittedly, I am not a fan of night running. Once it gets dark, I have to forcibly fight the feeling of just wanting to be done. It’s too monotonous. I enjoy the views. I am solar-powered. I was entering the realm where my hundred-mile demons have taken up a 14-year residence and have ignored all eviction notices.

From Glade Creek it is an 8-mile, mostly gradual climb on dirt road to the Wagner Butte trailhead. I was still running most of the ups, and moving well, which at this point in the game meant a 10 to 12-minute pace. My confidence was still soaring. Somewhere around Mile 77, I heard a noise behind us and turned to see a single light coming at us like a freight train. I remembered seeing this guy up near the front in the morning, never passed him during the day, and had assumed he was the frontrunner I heard had been crucified by the effort early and dropped. At any rate, he had resurrected himself in a scarcely believable way and went by us like we were walking. I made no effort to keep him in sight, as he was obviously operating in a different sphere. It didn’t even bother me. Was I starting a subtle slide from racer to runner status, or simply being sensible?

A few miles later another runner passed, at a more reasonable pace, and I purposely kept him in sight. Eighty miles deep and I still had some competitive fire left. This was new territory.

The Runner

At Mile 82 we turned onto the Wagner Butte trail and the reality of the third and final “epic” climb of the race hit with a gravity that felt much stronger than our planet’s pull of 9.81 meters per second. Your perception of things is much changed when it’s dark, cold, after midnight and you’ve been at it for over 18 hours, but the lower section of this trail felt rougher and steeper than anything I’d encountered all day. Switchbacks had seemingly been eliminated in favor of the plumb line. My legs immediately lost power and switched gears to that all-too-familiar 2 mph all-out effort.

The climb eased on the out-and-back section to the top of the butte, and when I came upon the two returning runners who had passed me on the road, I realized they weren’t all that far ahead. They were still within range.

The final rock pile to negotiate at the top of the butte was nothing short of comical in my unsteady state, requiring the jettisoning of my handheld bottles and the use of four points of contact. The view of the city lights far below in the Rogue Valley was spectacular, but it also seemed a silent yet poignant statement illuminating the fact there were still 14 miles and a healthy dose of quad-busting descent to go.

On the final trail leg from Wagner Glade to the aid at Road 2060, I entered what I refer to as the Bermuda Triangle of 100s. It involves the distortion of distance and the tweaking of time and wreaks havoc on your mental state. This 2.3-mile-long section felt like 5, and the near hour it took felt like two. I was still running some, but the trail was steep in places and seemed as though it had just been hacked out of the hillside the day before. After what felt like an eternity, the welcoming lights of the aid station finally appeared.

The Survivor

I had managed to maintain my every-30-minutes fueling plan (along with a Salt Stick cap and a Hammer Nutrition anti-fatigue cap every hour) with only one or two lapses, but somewhere along the Wagner Butte trail my body seemed to stop responding in a tangible manner to the calories. My stomach felt solid all the way to the finish line, and I never experienced a bonk but was definitely moving much more slowly now. However, in spite of the damage inflicted by Miles 82 through 90, I was still moving better than I ever had this late in the game, and sub-21 or 22 hours on a tough course remained on the radar.

I lingered long enough at the Mile 90 aid station to wolf down a grilled cheese and joke around with Carly Koerner, the wife of race director Hal Koerner, and JB Benna, the ultrarunner and documentary filmmaker. Despite my frustration at the endlessness of the previous section and my inability to “race” anymore, I was still in good spirits. That all changed quicker than a fast-twitch muscle fiber contraction.

As Dave and I started walking down the road, my feet immediately became the center of my attention. They hurt like hell. I shuffled a hundred yards, then slowed again to a hobble. I had noticed a few miles back that my shoes felt a bit tight, a sure sign that my feet had swollen. The pain increased rapidly to a point where running was out of the question. It felt like all of the nerve endings on the bottoms of my feet responsible for excessive pressure detection had suddenly redlined. It was physically excruciating to walk and mentally excruciating to be walking down a smooth, almost flat five-mile stretch of dirt road. With every step I had to quell the overwhelming desire to lie down on the ground simply to take the pressure of my body weight off my feet.

And I knew it would get worse before it got over. From my brief stint living in Ashland, I was all too aware of what awaited on the final four-mile Hitt Road descent into town and the finish. I was moving so slowly now that a shiver-inducing chill crept into my core as the waste heat of energy conversion dramatically dwindled. I began to blow off eating and drinking as the classic “%$#@ it” attitude set in.

Amazingly, nobody passed me until we started down Hitt Road. When each of the three runners did pass me, that bumped me into eighth place. I did not care. I was deep in the recesses of survivor mode, detached from the experience that was still happening. Besides, as mentioned earlier, I was never concerned about place so much as finishing in racer/runner mode for the first time. That one burning desire had evaporated quicker than water in the desert less than ten miles from the finish.

We hit pavement, steep downhill pavement. Brutal. Just as the seeming impossibility of the clock ticking past 24 hours loomed larger than a harvest moon on the faintly lit eastern horizon, we turned a corner and for the first time in 20 miles a landmark appeared sooner than expected…the finish line. 23:51:48. Almost four hours slower than the pace I was comfortably on for over 75 miles.

As I laid down on a cot in Pioneer Hall, immensely grateful to have zero psi on my feet, my thoughts randomly wandered to a line from one of my favorite Neil Young songs, “On The Way Home”:

“Though we rush ahead to save our time, we are only what we feel.”

The Aftermath

A mere four days after crossing yet another hundred mile finish line in a confusing state of both elation and profound disappointment at coming up short once again, after saying to myself every mile of the final ten, “I’m done with this. This succumbing to slow-motion suffering every time is ridiculous. This is not fun. I’m not figuring out how to play this game,” I’m not only looking forward to my next ultra but my next hundred. Because the truth is, I think I am figuring it out, slowly but surely making that relentless forward progress toward a solution that adequately addresses all the variables in the complex calculus of one hundred miles on foot. As Ian Torrence says, “It is much more than putting one foot in front of the other.”

At Pine to Palm, I found myself running strongly far deeper into a hundred than I ever have. For eighty miles I didn’t have the slightest hiccup in any aspect of how my body was feeling. My stomach remained solid the entire way. No blisters worth mentioning. I have had virtually zero quad soreness post-race.

Yet I still stumbled mightily in the end. My posterior chain (hamstrings, calves, Achilles tendons) were debilitatingly stiff for two days post-race. And, most in need of an answer, what caused my dogs to transform into the hounds of hell in mere miles? This has happened to me before.

It has been a mind-numbingly low-angle learning curve for me in the hundred-mile arena. It is why I carry with me so much mystified respect for the Timothy Olsons of the sport (he defended his title in a sizzling 17:19), those who somehow have it dialed in the first mile of their first race. I may never figure it out. I may be, as AJW jokingly (I think!) said, a “head case.” Those last 30 miles ARE special, and they are because not only do you have to pay your dues in the first 70 to get to them, but because, once there, you will most likely have to suffer mightily (and voluntarily) at some point to get through them. So far they have always left me wondering where my mental toughness stands in relation to others. Are the problems and pain that I faced at the end really any different than anyone else’s? Were the guys who flew by me on Hitt Road at the end truly suffering like I was (and still hammering anyway), or were they somehow feeling like I did at Mile 75 this close to the finish?

And so I’ve come back full circle to what are essentially philosophical questions. I cannot literally get inside someone else’s head, truly know what they are feeling, experiencing. Obviously, some people suffer more gracefully than others. And in this game, some suffer much faster too. Beyond these generalizations, who can say? I either could not or would not run in the last 10 miles because of what I was feeling. Maybe someone else in the same exact situation, dealing with the same exact pain, would have. I’ll never know.

What I do know is that I am still fascinated by the process and will continue to experiment in the quest for the breakthrough race. It may never happen. Maybe I am already maxing out my potential at this distance. I know as surely as the sun will rise tomorrow that if I dedicated every fiber of my being to training to run a sub-4-minute mile that it would absolutely never happen. I KNOW this. But the same can’t be said for, say, a 17-hour Western States 100 or a 19-hour Pine to Palm. As unlikely as they seem based on my prior performances, they are not impossibilities. The door remains open until I, or fate, say it is closed, and I won’t close it until I’m no longer enjoying the lifestyle. And every time I lace up my shoes and head out the door for a run, I can’t imagine my life without it.

***

My sincere thanks go to Jeff for sharing his report on this blog. Click here to read an earlier Q&A with Jeff, which includes his trail-running recommendations for the Eastern Sierra. Click here to read more about running around Southern Oregon and Pine to Palm’s Race Director Hal Koerner.

[…] Gilligan, whom I know and like. I felt truly saddened by it all. My friend from the Eastern Sierra, Jeff Kozak, put it well when he wrote on Facebook recently, ”About halfway through the comment thread […]