A widely reported study released last September showed that 55 percent of Americans believe in angels. I took that as another sign of our country’s slide toward anti-intellectual lunacy. Even as a churchgoer, I believe in angels as allegory, not as actual messengers of the divine. But I’ve spent the last couple of days thinking more about angels, as might be expected in this season of Advent, and have become more open minded about the possible existence of angels, loosely defined. It was the December 20 Rodeo Beach 50K more than the holiday season that sparked these thoughts.

As I sat in church Sunday morning surrounded by larger-than-life artistic representations of angels and singing carols about angels, I couldn’t stop thinking about the serendipitous confluence of people who greeted me at the start of the previous day’s run in the Marin Headlands, along with a strange, sad reunion that took place the day before the race.

I went with Morgan to this low-key Pacific Coast Trail Runs event not expecting to know many people and not feeling very motivated to run hard. I approached the event as a year-end run/hike in a glorious natural setting — a date with my husband, an ultra version of a walk in the park — not as a race in which I’d push the pace.

But then I saw Jim, with whom I ran my first-ever track workouts and trail runs in 1994. And Jeff, aka Dr. Mann, the orthopedist who diagnosed my fracture in June and reassured me that I would run again. And Samantha, a team member on the Calistoga–Santa Cruz relay in 2003, who listened and kept me laughing while I opened up to her about personal problems. And Roberta, whom I didn’t even know when she surged to my side in the 2005 Primo’s Half Marathon and murmured, “Stick with me,” and I did, and she coaxed me to a sub-1:29 PR. And Alita, who helped me stay involved with the Students Run Oakland program to coach teenagers to run a marathon, because if she could deal with all the setbacks and inconveniences of the program then so could I. And, not to be taken for granted, there was Morgan, who has put up with me and loved me unconditionally for more than half my life. They were all there, along with others I recognized, and I felt unexpectedly supported and energized. Their presence reminded me of how far I have come and how life becomes richer more from relationships than from money.

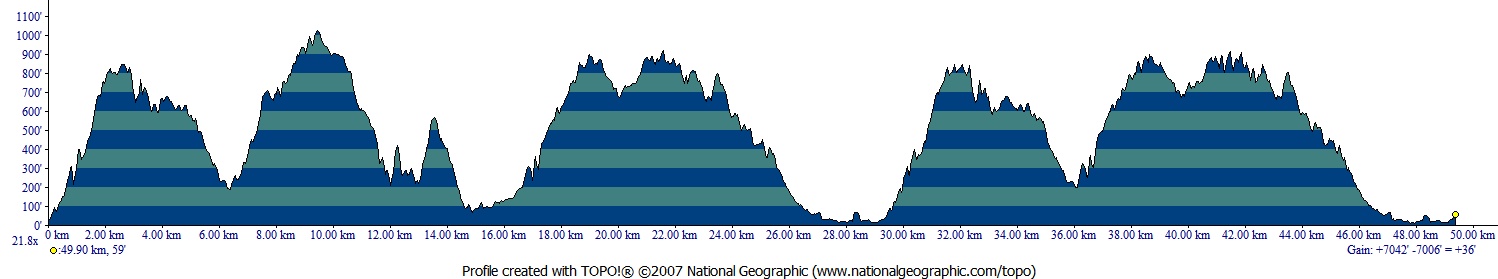

I rekindled the notion that I could perhaps break 5 hours on the course. A 10K in one hour should be do-able, even on hills and multiplied by 5, right? Earlier I had shelved this goal, however, given the course’s jagged profile (nearly 6000 feet of elevation gain) and my relatively low mileage for the past six months. Five-and-a-half hours would be more realistic and enjoyable.

When I think back on the run, I don’t recall it chronologically as much as I remember details — the frost crystallized on the wooden bridge, the Golden Gate’s towers peaking behind the mountain, the ladder-like wooden steps that carved stairways from the coast to hilltops, the emerald meadow by the beach. I was trying and succeeding in employing a trick that helps me run mindfully, by which I mean deliberately paying attention to the moment that I’m in rather than ruminating about the miles already run or anxiously anticipating those still to come. The trick is to pretend you’re running with a visually impaired person at your elbow, and you have to keep up a dialogue that describes the setting so that the person would be able to follow. You wind up saying things in your head such as, “There’s a eucalyptus tree on the left with peeling bark that shows lighter shades of gray and tan underneath, and the trail curves like a hairpin here so we see the coastline and Golden Gate again …” Even when part of your mind spins off in reverie, this trick forces you to bring it back, pay attention and appreciate the details. You try to care only about the stretch of trail you can see, and you take what the trail gives you.

I was able to employ that trick for most of the race, and run better because of it, because of what happened the previous afternoon.

I was in the 41st Avenue Oakland branch of the post office with my son, and the place was packed, the line barely moving. I had to ship a box to Thailand for a 12-year-old orphan we “adopted” through church, which meant we had to pick out as many school supplies, toys and candy as could fit in an 11x14x3 box. Feeling more put-upon than benevolent, I fumed at the inconvenience and felt skeptical that this box actually would make it to the boy whose picture we received. Then a man and his son walked in and took the spot behind us in line.

I recognized the man, who is probably in his mid-40s, from somewhere — over 6 feet tall, fair skinned and very fit, dressed in athletic clothes and running shoes — and it seemed odd he was wearing sunglasses and carrying the kind of long white cane that a blind person uses. I didn’t believe he was blind. There was something so easygoing about how he talked and moved with his son, who was about 11 or 12, and so healthy and attractive about his appearance that I convinced myself they must be conducting some kind of science project for the kid’s school, perhaps a sensory-deprivation or team-building experiment. I stole some glances but then quickly looked away, believing he could see me behind his sunglasses. We stood there, and I listened.

The son kept describing the scene to his dad. “There are three workers behind the windows, and there’s a line of Christmas cards taped on the wall behind them. One has a puppy wearing a Santa hat.” The dad smiled and nodded, and I felt my throat tighten. The boy reached out for his father’s elbow to guide him forward. I let myself look at the man longer, realizing he really couldn’t see, until it came back to me how I knew him.

We had hiked together a year ago, on a perfectly clear day, along with a couple dozen Cub Scouts and their parents. We climbed all the way to the big “C” behind the campanile at UC Berkeley, looking out over the marina, Bay Bridge and beyond, and he and I sat side by side while the boys played and posed for photos. We were in a eucalyptus grove on a steep hill, sitting on a metal utility structure covered with graffiti and littered with empty beer bottles. The conversation started slowly, revolving around the topic of Scouts and the view, and then it loosened up as he described his cycling and I revealed I’m a runner.

“Excuse me,” I said in line in the post office, before I knew what I was going to say, and the dad stood still while the boy looked at me. “I think I recognize you — are you in Scouts?” The dad said yes, his son was. “I believe we were on a hike together a year ago,” I said. “Remember, above Cal?”

The man nodded, and when he spoke there was a tremor in his voice as well as in the cane he held. “Yes, that’s right,” he said, and I tried to imagine how I would feel — caught off guard, vulnerable — if I couldn’t see a person who recognized me. “I’ve lost my sight since then,” he said.

“I see,” I said, and regretted my choice of phrase. But I couldn’t backpedal. I made small talk with the boy, asking him about Scouts and school, and then for whatever reason I said to the dad, “I recall you talked about cycling. You cycled a lot.”

His voice was steadier when he said, “I still do, but now it’s tandem.” He filled in the awkward pause by explaining, “I had surgery nine months ago, and an unintended consequence was that I couldn’t see afterward. The good news is they got the tumor out and it’s okay.”

What do you say in a situation like that, when you’re blinking back tears and worried that your pity will make the person feel worse? “I am so sorry,” I said. “I can’t imagine.” I shifted back to the safety of small talk and wished them well.

I ran hard at the Rodeo Beach 50K as I tried to soak up the sights and make the most of whatever stretch of trail I was in. I sprinted the final 5K as best I could and broke 5 hours by 31 seconds (4:59:29) to finish first woman and ninth overall.

When we say to someone, “You’re an angel,” what do we mean? Often it’s a statement of gratitude that the person unexpectedly acted in a way or gave something to us that helped us transcend the negativity or banality of the moment. They are uplifting; they help us gain a perspective that inspires us to be more loving, selfless and courageous. I can’t claim that these interpersonal connections are some kind of herald of a holy spirit; the God I believe in is too mysterious and abstract, and too universal to fit into any single religion, for me ever to believe there’s a divine micromanager who dispenses miracles and guides angels the way Santa fulfills wishes and directs elves. But I’m more appreciative of those who cross my path and act like an angel, and more attuned to a spirit in our connection.

Sarah,

This is absolutely lovely. Wonderfully muted (you don’t lean too heavily on your own metaphor) and therefore all the more moving. Congrats on the time, by the way (I don’t see how you keep managing to run faster and faster). Anyway, sweet story. Great start to my Christmas eve.

Thanks!

A message like this from my big brother is a great start to my Christmas eve! Thank you — your praise means more than you know.

Wow, Sarah, this brought tears to my eyes. You remind us all how important it is to stay mindful every moment we can, and to absorb the sights that await us around every corner.

Thank you, Kitty. I hope you know — you should know, anyway — that you’ve been an angel to me.